Yeager Statue Dedication

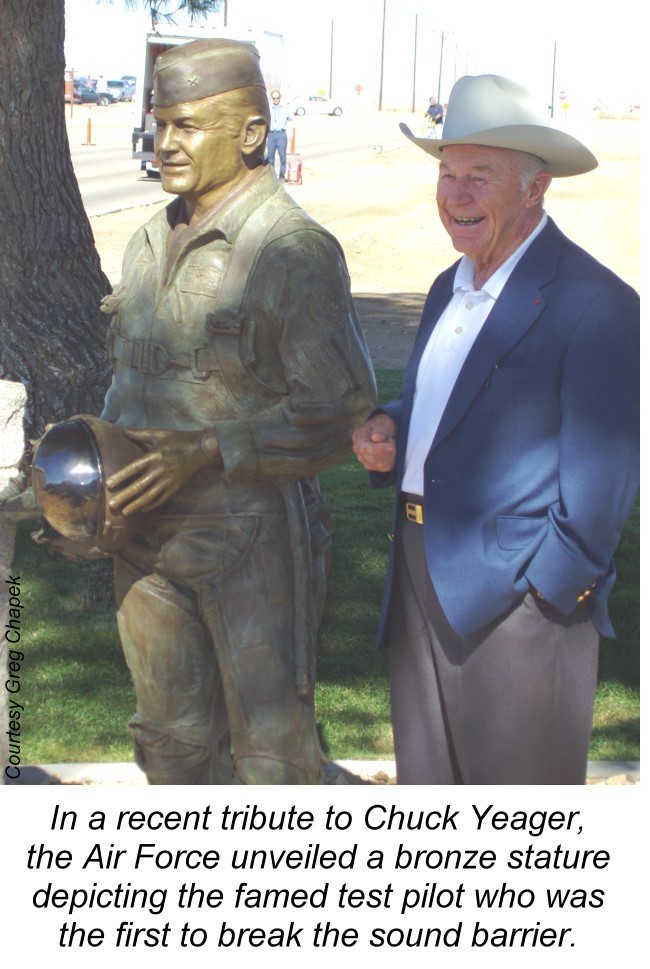

In a recent tribute to Brig. Gen. Chuck Yeager, the Air Force unveiled a bronze statue depicting the famed test pilot who was the first to break the sound barrier. The ceremony took place on August 30 at Sound Barrier Park, located near the Air Force Test Pilots School, which Yeager commanded during his distinguished Air Force career of more than three decades. The park was dedicated in 1988, with the placement of a stone monument commemorating his barrier-busting flight of Oct. 14, 1947. It’s located on Yeager Boulevard, so named in 1997 at the 50th anniversary festivities of his historic flight.

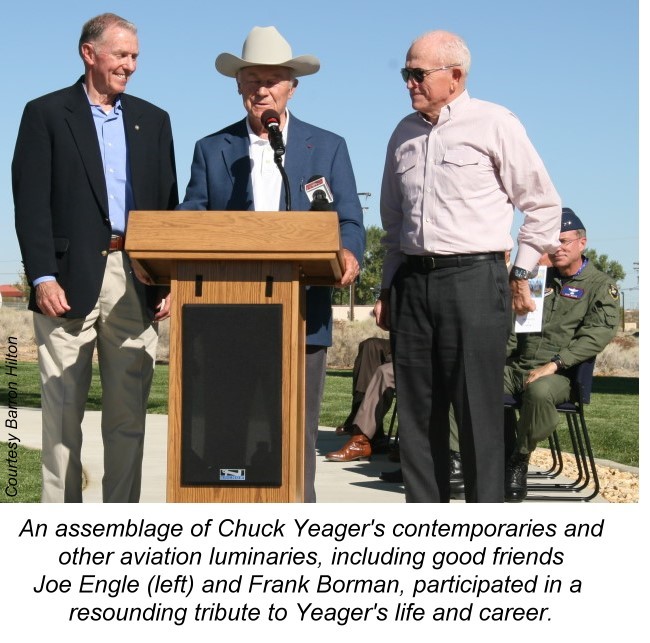

Under the early morning sun, and in the soothing shade of the large cottonwood trees of Sound Barrier Park, an assemblage of Yeager’s contemporaries and other aviation luminaries participated in a resounding tribute to his life and career. A pair of F-16s laid down a sonic boom over the park to open the event, to the delight of approximately 200 in attendance.

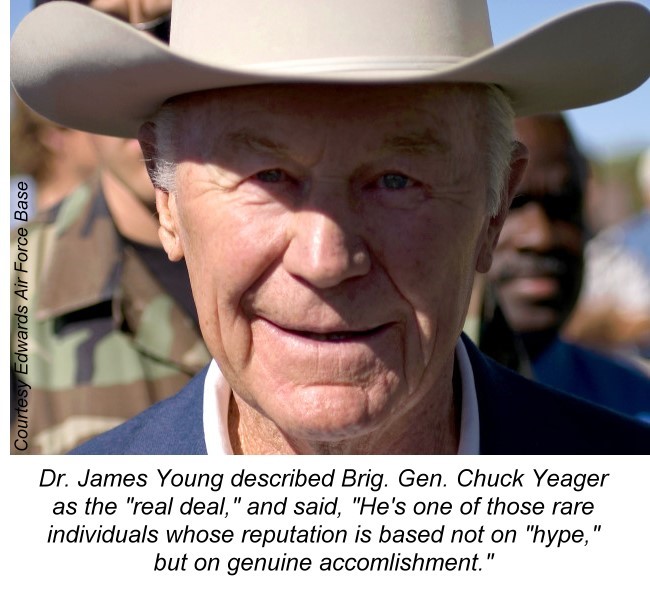

Dr. James Young, well-known author and historian, spoke eloquently about the life and accomplishments of Chuck Yeager, by sharing his own insights, and by relaying the commemorations of others who have known him.

“I’ve known Gen. Yeager now for 26 years, and I think I can say with some conviction that in an age of media-made heroes, he’s the ‘real deal’—one of those rare individuals whose reputation is based not on ‘hype,’ but on genuine accomplishment,” Young said. “He’s a real down-to-earth kind of guy, not some sort of unapproachable demi-god.”

Young shared insight from Maj. Gen. Fred Ascani, who has known Yeager for more than 60 years, since Yeager worked under him as a test pilot at Wright Field and at Edwards, and as a fighter squadron commander in Europe.

“Yeager flies an airplane as if he’s welded to it—as if he’s an integral part of it,” he said. “His ‘feel’ for any strange airplane is instinctive, intuitive and as natural as if he’d flown it for a 100 or more hours. The fact that he was absolutely fearless in his pursuit of technical knowledge was an added plus. One thought comes to my mind whenever I think of Chuck, and that is: no one, earthbound or ethereal, will ever be a clone of Yeager. Never, ever!”

Speaking of the technical abilities of Yeager, Young had the following insights from Dick Frost, the Bell Aerospace flight test engineer who worked with Yeager on the X-1 Program.

“I’d been a test pilot and I’d worked with some of the best in the business, but there was something special about Chuck that immediately set him apart from the rest,” he said. “What set Chuck apart was his unquenchable thirst for knowledge. He wanted to learn everything he possibly could about the airplane and its systems. He asked absolutely all the right questions and even a few I hadn’t thought of. He wasn’t a trained engineer, but he quickly grasped and mastered the most technical concepts, and he skillfully put that knowledge to work once he got in the cockpit.”

According to Young, Lt. Col. Jack Ridley, the Cal Tech graduate who worked with Yeager on the X-1 and other programs, put it succinctly: “Chuck never studied engineering, but he blots the stuff up as fast as it’s poured.”

Maj. Gen. Curtis Bedke, current commander of the Air Force Flight Test Center, fondly remarked, “General Yeager inspires all of us. When he retired, he didn’t leave us behind. He continues as an advisor to many commanders at Edwards AFB, and we hope to have many, many, many more years of his friendship. He’s been called a legend, a hero, the real deal, the most righteous of all those with the right stuff.”

To lighten up the moment, Bedke remarked on Yeager’s human side. Giving an example of his sharp wit and penchant for plain speaking, he described an all-too-typical encounter between Yeager and an admirer in an airport lounge. To the admirer’s question, “Are you who I think you are?’ he replied, “How do I KNOW who YOU THINK I am?!’”

In order to trace the roots of Yeager’s somewhat colorful character back to his parents, Bedke told the story of the scene at the White House when he received the Collier Trophy.

“His father, a loyal Republican, refused to shake President Truman’s hand,” he said. “His mother covered by sharing recipes with the president.”

Finally, to make sure everyone appreciated the unaffected practicality of the man, he confirmed that Yeager “used the Collier Trophy for storage of bolts and nuts in his garage.”

Gen. Yeager, looking tall and especially distinctive in his brilliant white Stetson, took the podium to thank those in attendance, the Air Force, and the statue benefactors.

“I’ve received a lot of honors. The ones coming from the flight test center are the ones that really get to me,” the 83-year-old retired brigadier general said. “I want to thank Bruce Fite, who donated the statue, for his generosity. He was a Marine fighter pilot—how’s that for inter-service cooperation?”

Many of Yeager’s best friends, mentors and protégés were in attendance. He told some stories about how they helped shape his career. Describing his post-WWII encounter with Bob Hoover, he said, “Guys didn’t try to jump me, ’cause I could wax their fannies. So I was pretty surprised when a P-38 jumped me and we ended up in a draw. I landed and went over to the P-38 to see who was so good, and out got this lanky, thin R. Hoover. I was a fighter pilot and a bit ragged on the edges. Bob Hoover and I flew a lot of air shows and I learned precision flying from him.”

Yeager was a role model and mentor to many distinguished test pilots, such as former X-15 pilot and astronaut Joe Engle and Apollo 8 Commander Frank Borman, who attended the ceremony.

“I’m very proud of two of my students: Joe Engle and Frank Borman,” he said, asking them to join him at the podium.

“For nearly a half century, Gen. Yeager has been my role model, inspiration, tutor, comrade fighter/test pilot-in-arms, military commander, and most valued personal friend,” said Engle. “Few people have a reputation like his to live up to. Fewer still are able to live up to that reputation. I’m extremely fortunate in that my career path has allowed me to fly and serve with him for a span of more than 40 years. This has given me a unique opportunity to learn from a master.”

Commenting about the transfer of astronaut training and space mission command from the Air Force to NASA in the 1960s, Yeager said, “If the Air Force had retained responsibility for space exploration and flight, we’d be further along and wouldn’t have the bureaucratic problems NASA has faced throughout its history.”

He then had some important stories to tell about how his insatiable curiosity for every detail about an airplane’s design and performance outside its stated limits saved lives—most importantly his own.

“For instance, I was the test pilot on the B-47, doing the heavyweight work on the airplane,” he recalled. “I was doing a roll over a friend of mine’s house at Lee Vining, doing about 440 knots. I was going to roll to the left and the airplane rolled to the right without me. When I put the aileron in, it twisted the wing and made the airplane role in the opposite direction. We put out a NOTAM, and that afternoon I instructed Joe Wolf: ‘DON’T exceed 420 knots, whatever you do.’ Later, he was buzzing the base housing and he must have been doing 440, ’cause he hit inverted on the base, killing himself and his copilot. Man, that’s bad.”

In another example, Yeager related, “I was testing the F-86 and we had five to six accidents already. I pulled up about 3 G’s in a roll and found out that the aileron locked up. I pulled back from 3 G’s and it unlocked.

I did it again, and it locked up again. I left off the G’s and it unlocked. That’s not good. Up ’til then, we had lost six and didn’t know why. So I went to Gen. Boyd and said, ‘I have an airplane that’s got the same problem; we can finally find out what’s happening.’ Well, the bolt was installed in the aileron actuator the wrong way. It was supposed to be with the bolt head down, and the maintenance guys had thought it should be normal for it to be bolt head up. We went back to North American to verify that it was designed to be head down. I probably saved a few lives that way.”

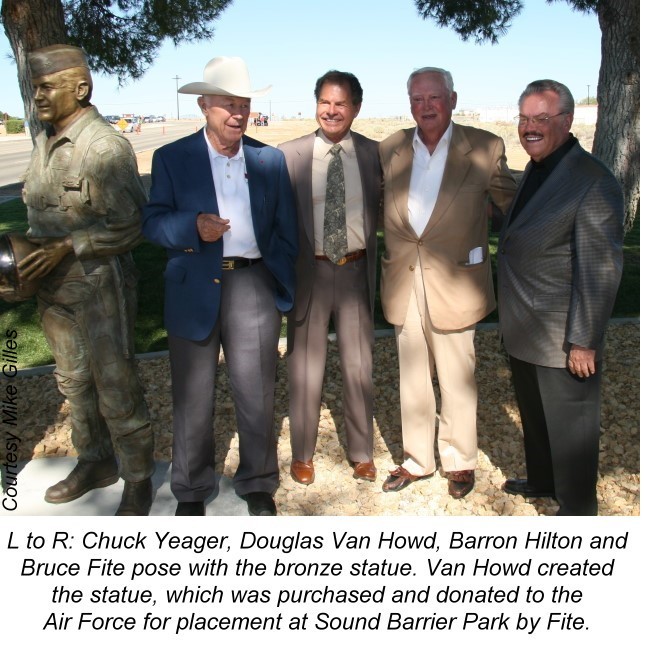

The 500-pound, larger-than-life bronze statue is a finely detailed depiction of Yeager in his flight suit, holding his visored flight helmet, as he appeared ready to fly in his heydays at Edwards. Sculptor Douglas Van Howd, who worked as a White House artist in the Reagan administration and has 43 monuments to his name, created it.

Speaking at the statue dedication, Van Howd said, “I first met Chuck Yeager at a three-shot goose hunt in California. I was partnered with Roy Rogers and we were on Chuck’s team. He placed us in one area. We had been up late the night before, so we promptly fell asleep. The enemy (the birds) flew over and everyone wondered why they didn’t hear any shots from our area. Boy, were we roasted that night.”

Explaining how the statue project came to be, he said, “I had been after Chuck to do a bronze for probably 20 years. If it hadn’t been for my wife, Nancy, and for Chuck’s wife, Victoria, I don’t think it would have ever happened. I never thought I would be here, and it’s the most honored thing I’ve done.”

The statue was purchased and donated to the Air Force for placement at Sound Barrier Park by Sacramento developer Bruce Fite, a friend of Van Howd. Fite, who often flew into Edwards during his military career as a Marine Corps pilot, said, “Yeager has been my idol, and I just thought this was a fantastic privilege to donate the statue.”

Chuck Yeager is still active, flying P-51s, float planes, jets and the Husky. Since retirement from the Air Force, he finds more time for hunting and fishing. His nonprofit General Chuck Yeager Foundation is supporting programs to teach the ideals by which he has lived his life: honor, integrity, courage, duty and service.