Yeager Joins the Air Corps and Trains for War

By Shannon White

During his young life, Chuck Yeager spent countless hours scouring the hills around Hamlin, always searching for something new and wondering what was just over the next rise. Not much excitement ever found its way to Hamlin, though. Even when a Beechcraft bellied into a cornfield up on Mud River when he was 15, and Chuck and some friends rode their bicycles over to take a look, the kid whose name would become inextricably linked to the world of aviation was far from impressed.After receiving his diploma from Hamlin High School in June 1941, the curiosity that had permeated his childhood led Chuck to wonder what life was like outside his little corner of the world. In September, he decided to enter the military. The kid who was raised to honor his flag and family would find the transition to military life an easy one. He possessed an unwavering dedication to duty – to finishing what he started – and he signed up for a two-year hitch with the Army Air Corps.

Chuck was trained as an aircraft mechanic, and soon realized there were many similarities between aircraft and automobile engines. His knack for understanding machinery made it easy for him to troubleshoot and repair problems with an airplane. That interest would never wane, and it would play a crucial role throughout his career.

While serving as crew chief of an AT-11, he took his first ride in an airplane. It was less than enjoyable. Chuck rode in the backseat as the pilot practiced landings on one of California’s dry lakebeds, and he discovered the misery of motion sickness for the first time. The young corporal didn’t think there was much of a future for him in an airplane, but a new initiative to recruit pilots would help change his mind.

Before the U.S. entered World War II, the Air Corps required pilots-in-training to have two years of college and be 20 years of age. When they received their wings, they were commissioned as second lieutenants. In 1942, in an effort to train more pilots more quickly, the Flying Sergeant program was unveiled and the regulation was changed. Flying Sergeant candidates needed only to be 18 years old and have a high school diploma. Though he hadn’t been impressed with his first ride in an airplane, the Flying Sergeant program interested Chuck. Now qualified to enter the program, Chuck signed up in December 1942. He thought it would be fun, he recalled later. And besides, with three stripes he would get out of pulling guard duty.

The next year would mark a turning point in Chuck’s life. He was accepted into the Flying Sergeant program and was a standout from the beginning. He had remarkable 20/10 eyesight, tremendous physical coordination, and an uncanny ability to stay focused in stressful situations. Those traits coupled with a competitive streak and his understanding of machinery caught the attention of his instructors — and led him to fighter pilot training.

After receiving his wings in March 1943, Chuck headed for Tonopah, Nevada to join the 363rd Fighter Squadron, 357th Fighter Group. The group was newly formed and consisted mainly of commissioned officers who had been aviation cadets. The fact that he was the most junior officer in the squadron didn’t matter to Chuck, who logged as many (if not more) flying hours than anyone. The 357th trained in the Bell P-39 Airacobra, a fighter that was excellent at low altitude but had a tendency to be somewhat unstable.

The 357th moved from Tonopah to Santa Rosa, California in June 1943. Two months later, the training schedule took them to Oroville, California. When they arrived, Chuck and another Flight Officer were charged with arranging some entertainment. They went to the local USO office, and Chuck asked the very attractive young social director named Glennis Dickhouse if she could organize a dance for his squadron that evening.

“She looked so annoyed I thought she might throw me out,” he would recall later.

Chuck persisted, telling Glennis she needed to invite only 29 girls instead of 30 because he wanted to take her. The event was a success. By the time the group left for Casper, Wyoming in September, she had given him her picture and they promised to write.

Casper would be the last stop before the group left for war torn Europe. The 357th Fighter Group boarded the Queen Elizabeth shortly before Christmas 1943. Their destination: A small town on the eastern coast of England.

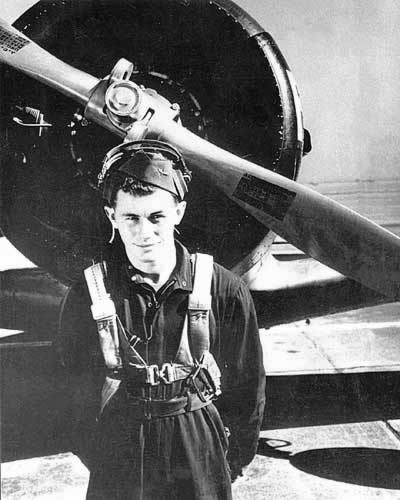

Yeager in front of a BT-13A during basic pilot training at Gardner Field, CA, December 1942.

Flight Officer Yeager’s P-39 over the Tonapah Bombing and Gunnery Range in April 1943.