1943-1945: The War Years

By Air Force Flight Test Center History Office, Dr. James Young, Chief Historian

Once in England and assigned to the Eighth Air Force, the unit was equipped with North American’s P-51 Mustang, soon to be recognized as the best all-around fighter plane of World War II. Yeager’s first mount was a P-51B, which he named Glamurus Glen after his fiancee, Glennis Faye Dickhouse. Yeager entered combat in February 1944 and claimed one Me 109 before being shot down on his eighth combat mission on 5 March. With the help of the French underground, he evaded capture and rejoined his unit in England. Carrying his appeal to return to combat all the way up the chain to Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, he resumed combat operations in August, flying Glamorous Glenn II, a P-51C with a “Malcolm Hood” canopy. Soon, Yeager was flying the P-51D model, which he named Glamorous Glen III, and in which he achieved most of his aerial victories. Blessed with exceptional 20/10 vision, Yeager had eyes that could “see forever.” He combined this advantage with cunning, concentration, relentless ferocity and superb piloting skills to rack up a final total of 12.5 aerial victories—including five Me109s on 12 October and four FW 190s on 27 November.

Of his 27 November experience, he recalled: “That day was a fighter pilot’s dream. In the midst of a wild sky, I knew that dogfighting was what I was born to do.” Yeager was ultimately promoted to captain during his tour in the European theater and, when he completed his final flight on 15 January 1945, he had totaled 64 combat missions for 270 hours. He married Glennis Faye Dickhouse, for whom his P-51B, -C and -D Mustangs were named, when he returned stateside in February 1945.

A trio of 363rd aces at Leiston, England, January 1945; Center: Captain Don Bochkay (13.75 victories); Right: Chuck Yeager (12.5 victories).

357th Fighter Group ace Chuck Yeager (Left).

Leiston Airfield, England 1944.

A rare in-flight photograph showing two German Me-109s.

Into the Lion’s Den: Combat Over Europe

By Shannon White

The 363rd Fighter Squadron completed its final two months of training at Casper, Wyoming. Before his unit headed east to depart for Europe, Chuck had arranged to spend a weekend in Reno with Glennis. Instead, he ended up in the base hospital at Casper. His P-39 caught fire during a training flight on 23 October and Chuck was forced to bail out. In doing so, he had fractured his back. He and Glennis would say their good-byes in Casper a few weeks later.

The entire 357th sailed for Europe aboard the Queen Elizabeth on 23 November, 1943. The Group was originally assigned to the 9th Air Force but once in England, they were reassigned and would become the first unit in the 8th Air Force to employ the new P-51 Mustang fighter.

A fast, sleek, and highly maneuverable design that went from the drawing board to the flight line in just 116 days, the Mustang included an indispensable element that would ultimately turn the tide of the war in Europe. Two 108-gallon external fuel tanks, one mounted beneath each wing, gave the nimble fighter a range that exceeded any of its predecessors. The pilots of the 357th would cut their teeth on the Mustang in the skies over Germany.

The air base at Leiston was just three miles from the North Sea coast near the village of Yoxford. When they set up housekeeping there in February 1944, the members of the 357th were surprised to hear an announcer on a German radio station welcome “The Yoxford Boys” to town.

The Group’s first combat mission was logged on 11 February, 1944. Flight Officer Chuck Yeager would score his first aerial victory a few weeks later on 4 March when he downed an Me-109 during one of the first daylight bombing raids over Berlin. But, as he soon learned, luck can change quickly in wartime.

The following day, 5 March 1944, Yeager was shot down while trying to make a head-on pass at a group of Fokke-Wolfe 190s during a raid on Bordeaux, France. Bailing out over Occupied territory was risky business. Even if he made it to the ground in one piece, Chuck knew his chances of avoiding German patrols were slim.

He waited until the last possible moment to open his parachute, then scanned the ground below as he descended. German troops seemed to be everywhere. After sweating out the ride down, he found himself in a forested area. Chuck rolled up his parachute and took cover in the heavy brush.

The next morning, as a French woodcutter made his way through the area, a pistol-wielding Chuck approached. His objective now was to avoid being captured at all costs and make his way into neutral Spain. He needed the help of the French underground if he was to succeed.

The startled woodcutter spoke no English, but understood that the young flier needed assistance. Soon, Chuck was under the watchful eyes of the Maquis – the French resistance movement. He spent the next few weeks traveling with the Maquis through the French countryside. He showed them how to set various timings for fuses on plastic explosives, something he had done years before with his Dad in the natural gas fields.

On 23 March, 1944, Chuck and three other downed American fliers were driven to the edge of the Pyrenees Mountains. The range forms a geographic barrier between France and Spain. Once on the other side, the men would be in neutral territory.

Chuck and a B-24 navigator would make the journey together. After four days of steady climbing through knee-deep snow and a relentless, freezing wind, the men were exhausted. They found a deserted cabin and decided to rest a while. The other airman hung his wet socks on a bush outside the cabin. He and Chuck were too tired to realize what a mistake that was.

Chuck was awakened by the sound of bullets hitting the cabin. A German patrol had passed by, seen the socks, and started shooting. The two men dove out a back window. Chuck threw his injured comrade on a snow-covered log slide and jumped on with him. The men ended up in a deep creek several thousand feet below the cabin. Once on the bank, Chuck tended to the other airman’s wound. Without Chuck he would have perished. Chuck then proceeded to drag his injured comrade back up the mountain.

Cold, wet, hungry, and with every muscle in his body aching, Chuck inched along. He did not stop for fear of falling asleep and letting go of his injured comrade. Finally, and practically without realizing it, Chuck reached the summit. Far below he could see a road. He pushed the unconscious airman down the slope and followed behind. Chuck left his injured comrade at the side of the road where border patrols could find him, and continued south. Now in Spain, he would soon have to turn himself in to the authorities.

Chuck Yeager With His Ground Crew

Yeager and Glennis

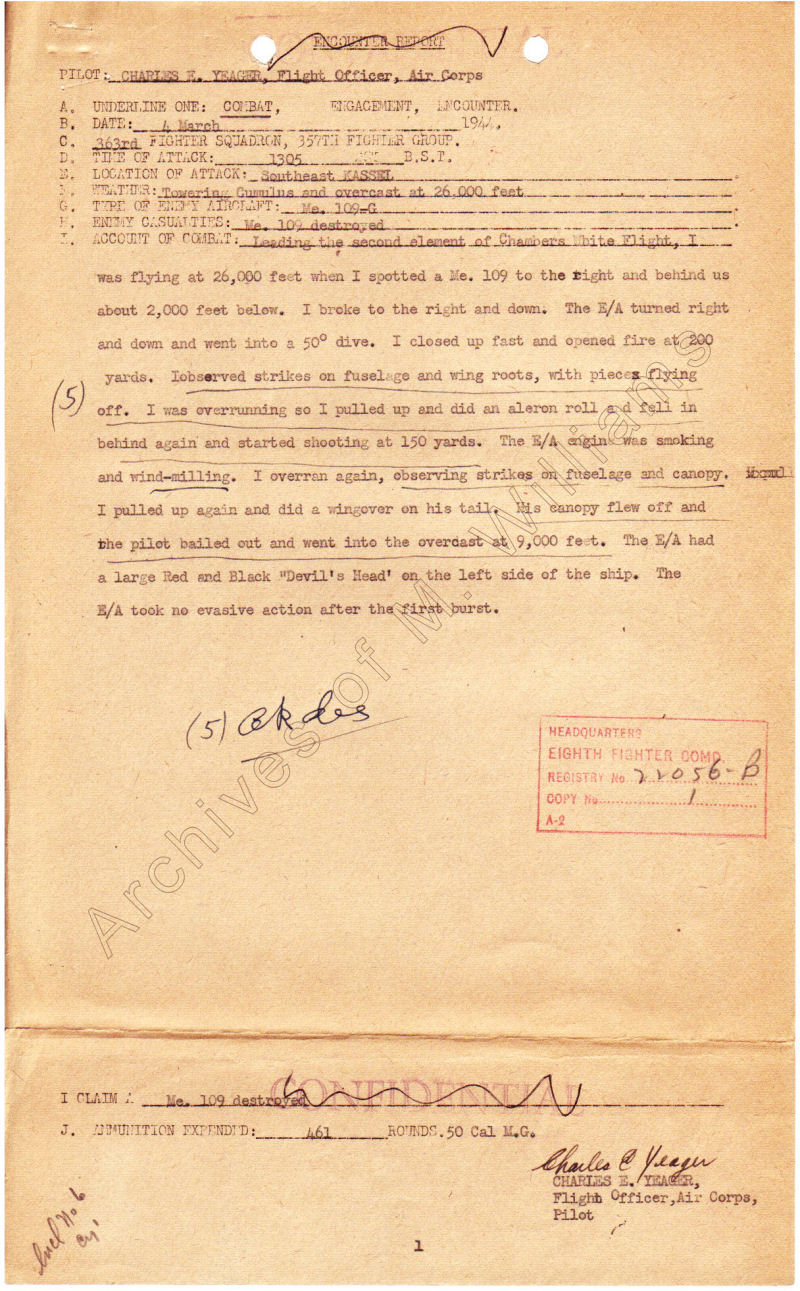

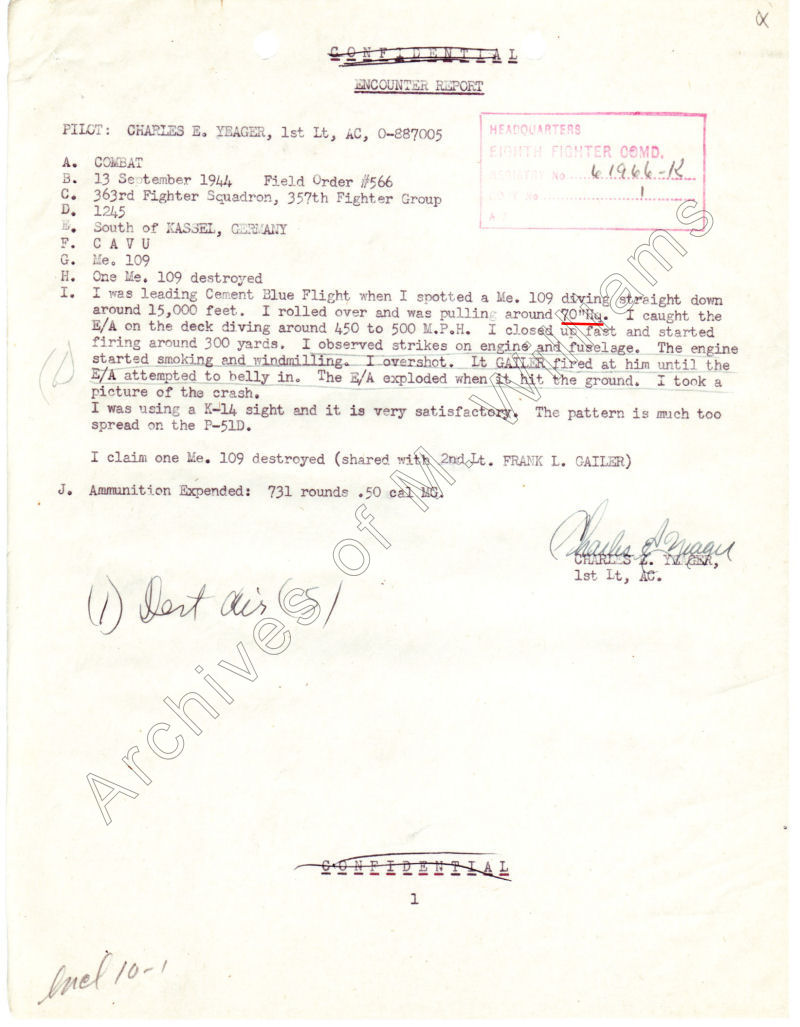

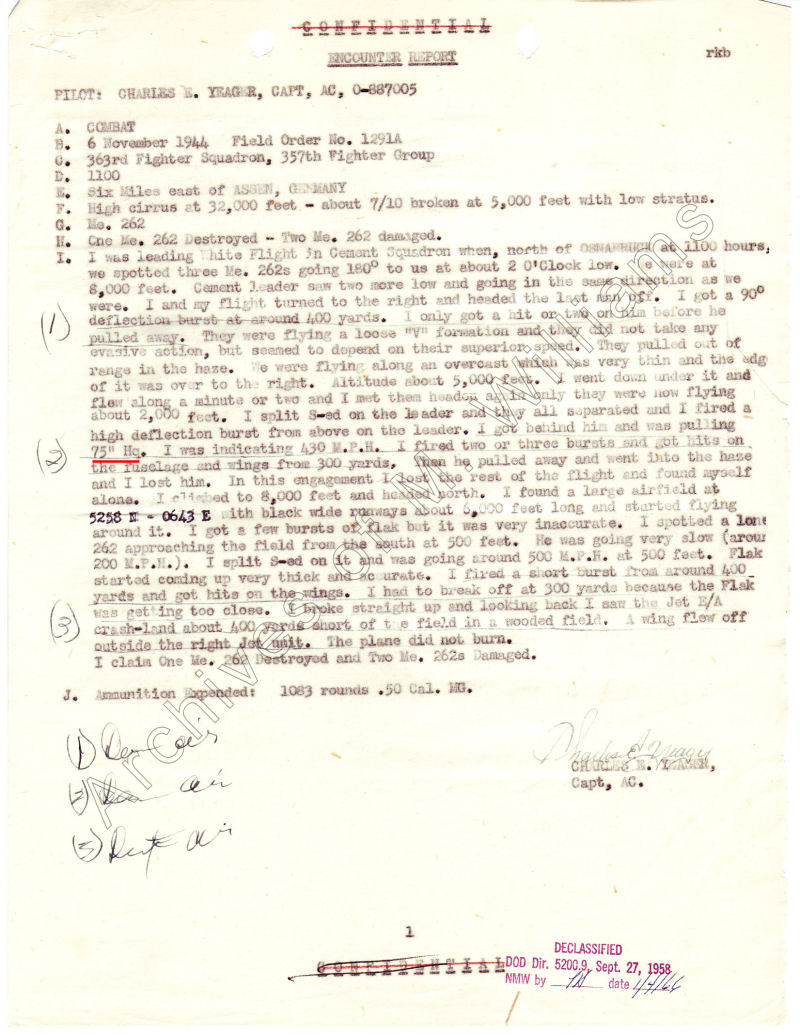

Yeager’s Combat Reports

First Air Victory:

The first combat Encounter Report filed by Flight Officer Charles (Chuck) E. Yeager described the destruction of an Me 109-G on March 4, 1944. The enemy pilot bailed out and disappeared into the overcast.

Escape from France:

Escape and Evasion Case File for Flight Officer Charles (Chuck) E. Yeager, 03/05/1944 – 05/15/1944. Describes being shot down while on a mission to Bordeaux and his heroic escape to Spain with the assistance of the Maquis. Includes vivid details that Flight Officer Yeager provided to British intelligence that would help other pilots evade and escape.

Back in Action:

Second combat Encounter Report by Flight Officer Charles (Chuck) E. Yeager, 13 September 1944. Describes his shared victory in his second Me 109 destruction, which crashed and exploded on the ground after also receiving hits from 2nd Lt. Frank Gailer’s P-51D.

Five Victory ME-109 Report:

1st Lt. Charles E. Yeager’s combat encounter report for the 12th of October 1944, the day he downed five Me 109s.

Four Victory FW-190 Report:

Yeager’s combat encounter report for the 27th of November 1944, the day he downed four FW 190s.

Yeager Destroys Me 262:

The Encounter Report of Captain Yeager’s first destruction of an Me 262 jet fighter and damage to two Me 262′s. This report details the daring chase that separated Capt. Yeager from his squadron and the encounter near an enemy airfield. Capt Yeager shot the Me 262 down as it was on final approach to land at the enemy airfield. Yeager’s only option was to fly down the runway low and fast. Airfield defenses fired shots missing Yeager but hitting airfield defenses on the opposite side of the runway.

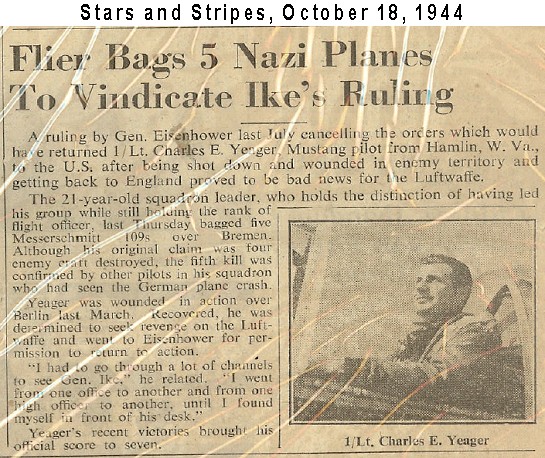

Air Force Stars and Stripes

The Air Force Stars and Stripes published a glowing article about Yeager’s the heroic air battle in which he destroyed the 5 ME-109’s, and “vindicated” Gen. Eisenhower’s allowing Yeager back into combat after being shot down on his eighth combat mission.

Yeager’s Last WWII Mission

Jan 15, 1945, was Yeager’s 61st and last WWII mission. He recalls with disappointment that he missed the biggest battle that day; fifty-seven German planes were destroyed by their squadron. Yeager, whose mission was to fly over the channel as “spare” with his WWII buddy Andy, decided to lead Andy on a tour of Switzerland where they dropped their wing tanks and playfully used them as ground targets for practice.

Yeager, shortly after he returned to combat in August 1944, climbing into the cockpit of his second Mustang, a P-51C he named "Glamorous Glenn II."

Capt. Chuck Yeager in the cockpit of his P-51D Mustang, late 1944.