1947-1954: Testing the Limits

By Air Force Flight Test Center History Office, Dr. James Young, Chief Historian

While his flights in the X-1 guaranteed celebrity, it was Yeager’s performance over the next seven years that earned him pre-eminence –indeed, legendary status– within his own peer group, the experimental test pilots at Edwards. Yeager has called these years his “golden age of flying and fun.” It was an age when the limits of time, space and the imagination were being dramatically expanded. And Edwards AFB was the place to be, the place where a whole stable of exotic research aircraft were probing the unknowns of flight and where new experimental prototypes appeared on the flight line in seemingly endless numbers.

He was one of the first two Air Force pilots to evaluate North American’s supersonic YF-100 prototype, as well as the initial production model F-100A. His report of serious flight control problems with the F-100A was soon borne out when a series of mishaps forced a redesign of the airplane.

He completed one of the first Air Force evaluations of Lockheed’s XF-104 just before departing for a European assignment in 1954. Less than seven years after first exceeding Mach 1, he was flying the prototype for America’s first Mach 2 operational jet fighter.

Chuck Yeager was in the middle of it, loving every minute. He became the test pilot of choice among engineers because he flew with such extraordinary precision that his data points were always right on target. He also demonstrated an unrivaled ability to quickly ferret out and understand an airplane’s flaws. Flying constantly at the edge of the envelope . . . and then beyond, at a time when accidents were far more common than they are today, Yeager repeatedly demonstrated an uncanny ability to coolly think his way through potentially catastrophic situations, take appropriate action, and bring his ship back.

A fighter pilot by training and instinct, Yeager nevertheless logged a lot of time in multi-engine bombers and transports. He had more hours in the Martin XB-51, for example, than any other Air Force pilot.

No high-powered sports car for Yeager! His weather beaten, pale blue Model A Ford was a familiar sight on the Edwards flight line.

From 27 September to 5 October 1953, Yeager was at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa. General Boyd was, by this time, commander of the Wright Air Development Center and he had requested that Yeager and Maj Tom Collins join him there so they could perform a complete evaluation of the first Russian MiG 15 to come into American hands. Yeager considered this “the most demanding assignment” he had faced up to that point in time. Under an extremely tight schedule, in wretched weather, he had to wring out what he called a “flying booby trap”–an unforgiving craft, susceptible to unexpected pitch-ups, fatal spins, and a host of other problems.

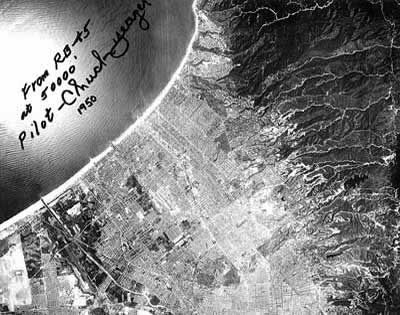

Santa Monica Bay, as viewed from 50,000 feet during the test of an RB-45 flown by Yeager in March 1950.

The Bell X-1A was powered by an uprated, 8,000-lb thrust XLR-11 rocket engine. At the time of Yeager’s epic flight, there was no provision for pilot egress. An ejection seat was subsequently installed.

He met the challenge, as he took the fighter up to more than 55,000 feet and, despite the fact that he knew he’d lose elevator control, he subsequently put it into a near vertical dive to achieve its 0.98 maximum Mach number. The tests confirmed that although the F-86 was a superior fighter, overall, the MiG had the advantage in terms of rate of climb, higher ceiling and better acceleration. General Boyd later reported: “The flight tests of the Russian MiG really demonstrated what Chuck Yeager was made of. It was extremely dangerous work, flying in horrible weather . . . Because of him, we now know more about this airplane than the Russians do.”

Yeager on the ramp at Edwards with the personnel and equipment required to support his flights in the Bell X-1A.

Yeager on the lakebed immediately after his wild ride in the X-1A on 12 December 1953.

After launch on 12 December 1953, Yeager lit his rocket engine in the Bell X-1A and pulled into a climb. At 62,000 feet, he started his pushover and finally leveled out at 76,000 feet and Mach 1.9. Using full thrust, he accelerated to Mach 2.44 (1650 mph). After he cut his engine, the X-1A started a slow roll and yaw to the left. As he corrected for this, it rolled sharply to the right. Another correction and it snapped to the left and tumbled violently out of control. He was encountering something new–something called inertia coupling.

The X-1A was “snapping and rolling and spinning” about all three axes and he took a beating in the cockpit as he plummeted more than 50,000 feet before somehow managing to recover to level flight at 25,000 feet.

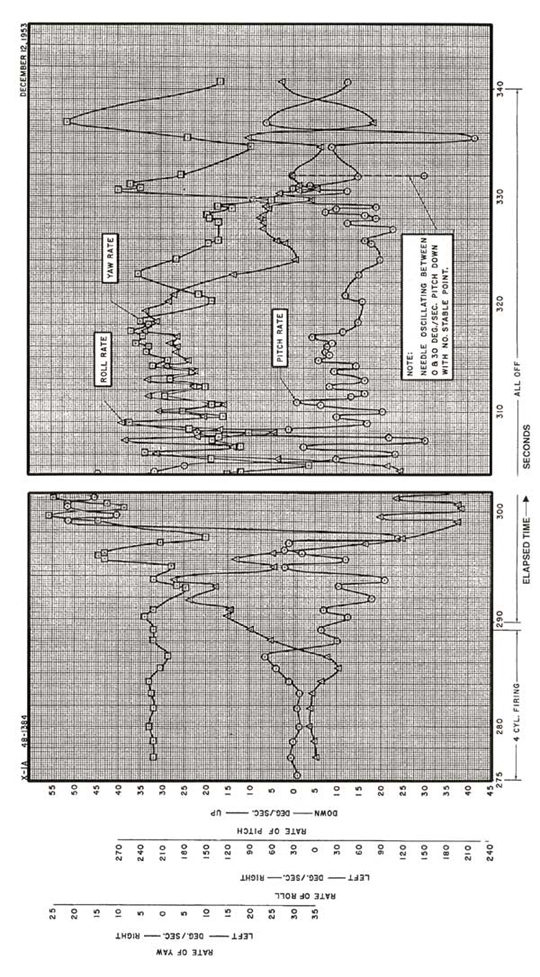

Bell X-1A Chart

Strip chart time histories for yaw, roll, and pitch rates during the first 50 seconds of Yeager’s tumble in the X-1A provide graphic evidence of what he experienced in the wildly gyrating airplane. Note: three seconds missing (301-304).

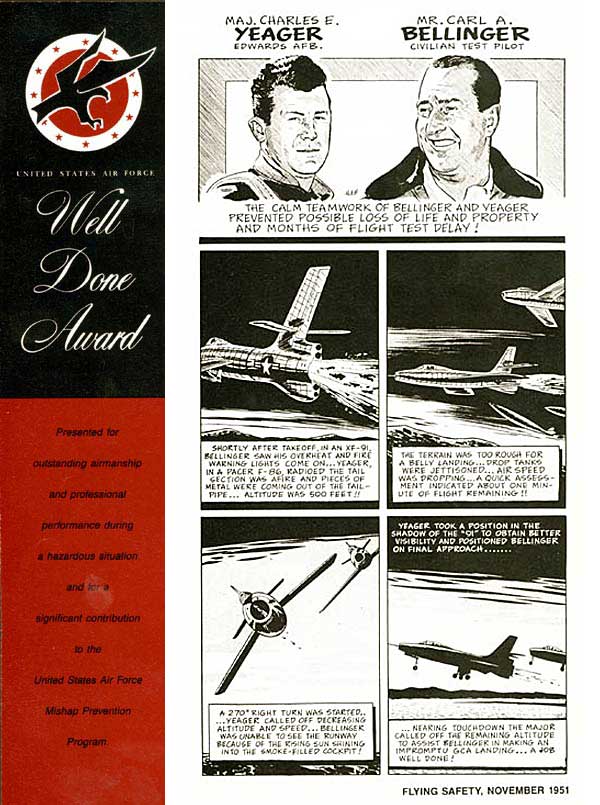

Well Done Award

Famed test pilot Carl Bellinger was one of many test pilots at Edwards who owed their lives to Yeager’s skills as a chase pilot. In an era when fatal accidents were still fairly common, Yeager never lost a pilot while he was flying chase.

Form 5

Yeager’s Form 5 for September 1950 was typical of his activities at Edwards from 1947-54 (and likely to give current-day test pilots causes for envy): 45 flights for 61 hours in 12 different types and models of prop and jet aircraft–including fighters, bombers, transports, trainers and an experimental research aircraft.

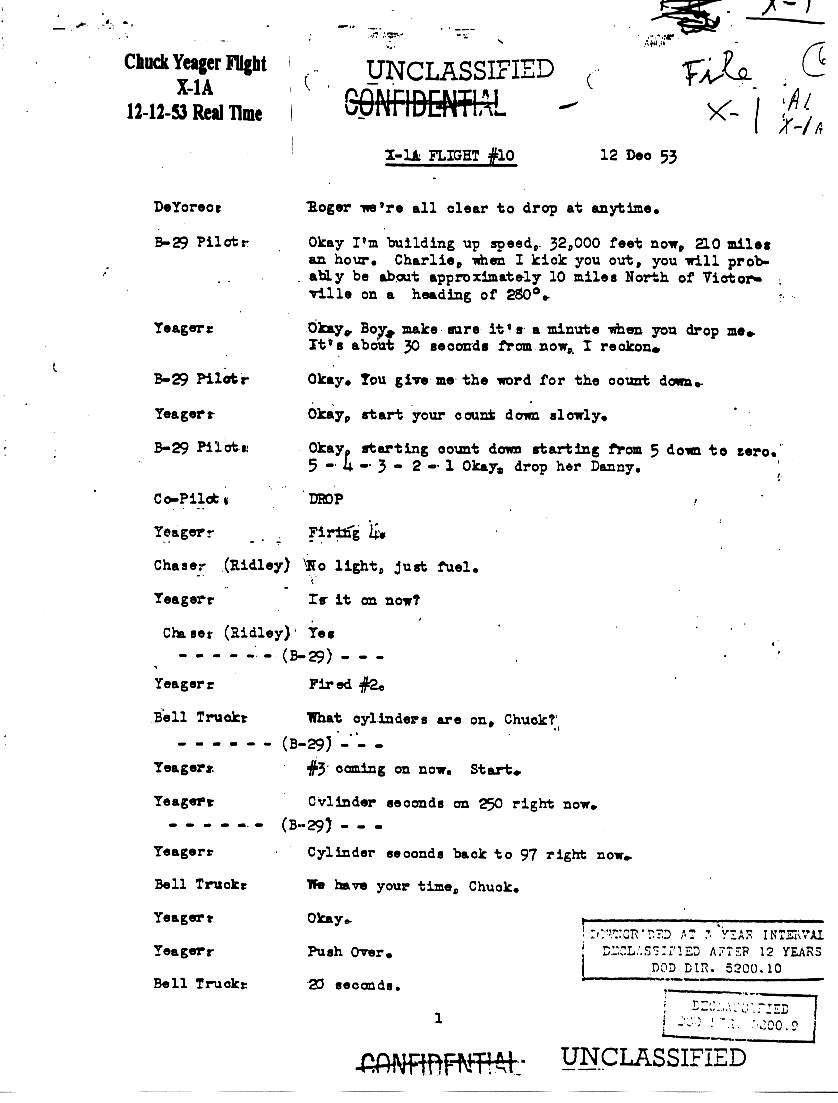

X-1A Flight Audio

Air-to-air and air-to-ground communications of Chuck Yeager’s record-setting wild ride in the Bell X-1A on December 12, 1953, were recorded and transcribed. This was Flight #10, in which Yeager set the speed record for a straight wing aircraft of Mach 2.44.

Yeager and Maj. Tom Collins at Kadena Air Base, October 1953.

Yeager with Maj. Gen Albert Boyd during the MiG-15 evaluations at Kadena Air Base, October 1953.

Yeager in the cockpit of the MiG 15. All of the gauges were based on the metric system, making them all virtually useless to him. He completed three missions in the airplane, logging 2 hours and 45 minutes of flying time.

Arrayed in USAF markings, the captured MiG 15 was evaluated during a series of flights at Kadena Air Base.

He was the first Air Force pilot to fly a delta-wing aircraft, the Convair XF-92A. Convair’s test pilot had refused to roll the airplane. Convair project engineer Bill Chana recalled: “On his very first flight, Chuck came in low over the lakebed doing a series of barrel rolls!”

Yeager served as Air Force project pilot for virtually all of the experimental “X-planes” at Edwards during that era, including the X-1, X-1A, X-3, X-4 and X-5.

Yeager flew chase for a number of milestone flights flown by other pilots. On 18 May 1953, for example, he flew chase for his close friend Jackie Cochran as she became the first female pilot to exceed the speed of sound in a Canadian-built F-86.

For his remarkable, record-breaking flight, Yeager was awarded the 1953 Harmon International Trophy by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. His good friend Jackie Cochran, who had become the first female pilot to exceed the speed of sound that year, won the award for women.