Germans at the Door – Escape and Evasion Continues

March 5, 1944 continued

I decided to stay put until dark. Several times I hear low-flying planes-Germans hunting for me. I’m sweating but stay well-hidden under thick brush. I saw a lot of farmland coming down and at night I’ll pop out of these woods long enough to raid some turnips and potatoes. I figure a French farmer is no match for a hungry hillbilly. But long before dark, it begins to rain, and there are no more search planes. I eat a stale chocolate bar from my survival kit.

Then I peek out and see a woodcutter shouldering a heavy az. I decide to rush him from behind and get that ax. Killing him if necessary. I jump him and he drops the ax, almost dead with fright. With eyes the size of quarters, he stares at the pistol I’m waving in his face. He speaks no English, so I talk at him like Tarzan: “Me American. Need help. Find underground.”

He jabbers back in excited French, and if I understand right, he tells me he will go get somebody who speaks English. I read his face, which is scared but friendly. He grins and nods when I say I’m an American. Puts a finger to his lips to whisper, “Boche,” then hurries off into the forest, after signaling me to stay hidden and wait for him to get back. I keep his ax and watch him run off; then I move across the path into a stand of big trees, wondering if I should take off or wait for him. Can I trust this guy?

Long before I see them, I hear returning footsteps. Definitely more than one person, but whether they are more than two. I can’t tell. It’s been ore than an hour since that woodcutter took off. I move back into the stand of trees and drop down. My pistol is pointing at the path. I won’t get very far if he’s brought a squad of German soldiers. I’m burrowed into the wet ground, my heart thudding like a five-hundred-pound bomb as the footsteps stop. My impulse is to turn tail and run, but I check it.

Then I hear a voice calling me in a whisper. “American, a friend is here. Come out.”

(Note from Victoria: Gen Yeager and I learned recently that F/O Yeager had approached the head of the Maquis for that area; M. LeFarge. Later, M. LeFarge’s son became mayor of Cours les Bains followed by Etienne Labardin, the man who held onto the window of General Yeager’s canopy for 70 years.)

First, they take me to a nearby house where a young woman’s husband had been conscripted by the Germans. The wife gave me her husband’s clothes, about my size.

Then the old man leads the way through the deepest, darkest part of the woods. German patrols are all around us, hunting for me. Several times we think we hear distant voices and scramble to hide in the brush. But soon we are circling a clearing, staying in the shadows of the pines, and I see a two-story stone farmhouse. The old man nudges me, bends low, and runs across the open field toward the house. I follow him, expecting to hear rifle shots any moment. I forget my wounded leg and move. He leads me to the back of the house, and I follow him into a barn, and up a ladder to the hayloft. He opens a door to a small room used to store tools and pitchforks, and pushes me in. Then he shuts the door, locks it, and begins pitching hay against my hiding place. I’m drenched in sweat. The small room is almost airless and pitch dark with barely room for me to sit. I’m trapped in this damned place and begin to wonder whether or not I’ve been trapped by the old guy: made a prisoner while he runs to get the Germans and maybe pick up a cash reward. I argue with myself about that lousy possibility, but not for long: there are German voices in that barn, and I hear them climbing the ladder to the hayloft.

My automatic is out, my finger on the trigger. The sounds are muffled but definite: they’re rummaging in the hay, stabbing into it with bayonets like in a war movie. They come close. I don’t know how long I sweat it out, but straining to hear, I hear nothing. I never hear them leave, if they have. Maybe they are just sitting out there, having a smoke, and playing a nasty game with me.

They come for me several hours later. I hear the sounds of hay being moved; by then, the .45 feels like it weighs fifty pounds, and it takes both of my aching hands to hold it. Before he opens the door, the old man wisely whispers: “It’s me. You’re okay. They’re gone.”

When he unlocks the door, I don’t know whether to hug him or shoot him. I’ve no idea what is going on. We move quickly from the barn into the farmhouse, and I’m amazed to see it is already dusk. He leads my up a flight of wooden stairs to the second floor, and we enter a bedroom where a woman is sitting up in bed, wrapped in a shawl and surrounded by medicine bottles. She’s about 55, with keen, intelligent eyes, and when she sees me, she begins to chuckle. “Why, you’re just a boy,” she exclaims. “My God, has America run out of men already?”

I tell her most pilots are young and that I’m 21. She speaks perfect English and begins to question me – my name and background. I shake my head when she asks me if I’m married, and her eyes narrow. “What about that?” she asks, pointing to my high-school ring, which I wear on my right hand, where Europeans wear wedding rings. I explain and she seems satisfied. “We must be very careful,” she says. “The Nazis are using English-speaking infiltrators to pose as downed American fliers.”

She’s satisfied that I’m not that I’m not a German, although she is puzzled by my West Virginia accent.

We hear Germans at the foot of the staircase. She motions to me to get under the bed. I scramble as fast as I can. The Germans enter her room. She has pulled up the covers and asks the Germans what do they want with a sick old woman?

Horrified, this is pre-penicillin and sickness is no joking matter, and embarrassed at their undignified barging in, they back-pedal, apologize, and leave.

Once they are gone, she says, “Our people will help you, but you must do exactly what you are told.”

If the Germans catch us, I would be sent to a prison camp, but they would be pushed against the stone wall of the farmhouse and shot on the spot. I’m taken down to the kitchen where a young girl feeds me soup, bread, and cheese, my first meal in more than 24 hours. I wolf it down. Later that night, the village doctor climbs the ladder to the hayloft, and I’m let out of my dark little cell long enough for him to pick the shrapnel from my hands and feet. The shrapnel puncture in my lower calf is not very deep. When he’s done, the doc makes a little speech in French, probably saying, “Hey, kid, your wounds are the least of your problems.”

The next night, LeFarge and I rode bikes to the nearest large town Casteljaloux.

(Victoria Yeager note:

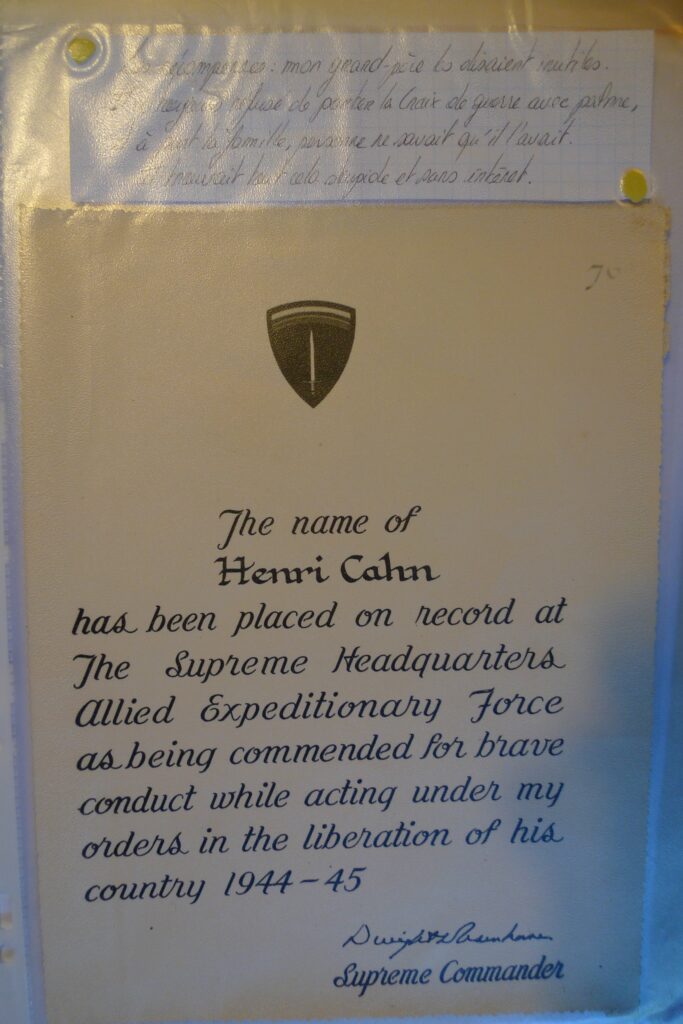

The doctor is Dr. Henri Cahn, a Jewish doctor who had been put in a French work camp from which he escaped. Near this camp, Allons, became a center for the French underground. The French underground members called him Dr. Henri or Dr. Henri Babbi to hide his ethnic background. He slept in his car in a different spot in the forest every night. The forest is based on sand and some quicksand. Dr. Henri’s son, Eric, now in his 70’s showed General Yeager and me the forests and we showed him the work camp which we had found. The beautiful building, former mansion, on the farm had clearly been used for cells and chains. The French milice (special police), trying to prove they were as good or better than the Nazis were even worse and more feared.

The Russian lady’s family had been very wealthy in Russia. During the Bolshevik Revolution, her family, leaving much of their wealth behind, had moved from Russia to Paris, France. Just before Paris fell to the Germans in 1940, she moved down to Cours les Bains area an hour or more southeast of Bordeaux. She ran a spa with sulfa hot springs, and this is where F/O Yeager was taken. General Yeager and I have visited this place. The original two-story area where the Russian lady first met F/O Yeager is no longer there and the spa is boarded up, but the rest of the house has been renovated by a young couple. The barn is still there and looks like it used to be a small church.)

- GCYI